Survivors of Sex Trafficking Share What It Means To Be Beautiful

Sex Trafficking

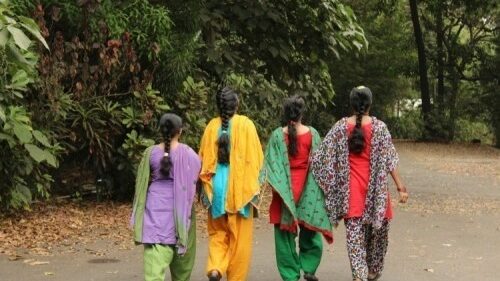

Every twenty-something woman has ideas on what it means to be beautiful. A small group of young women gathered in India’s largest city take turns musing, each one wearing a different palate of bright colors.

“Even if I put on make-up but am not pretty inside, it’s a waste of make-up!” exclaims Saba,* as she holds a corner of her green scarf in her hand and waves it as she speaks. “Women can be beautiful with make-up and without; inner beauty is also important.”

Two other young women in the group explain how they view this inner beauty. “I should keep good feelings for others,” one says; another adds, “If God helped us, blessed us, then inner beauty is to help others.”

These simple statements about finding beauty by helping others are remarkable. Less than two months ago, these four women were in desperate need of help themselves: They were trapped inside a brothel in Asia’s largest red-light district.

Since they were rescued, IJM social workers have been helping them redefine and reclaim who they are and what they want. This is the beginning of freedom.

Traffickers Target The Poor

The four young women were trafficked to Mumbai from different places and by different people, but their stories start with alarming similarity.

In Bangalore, Amal* had run away from her abusive husband after he beat her for having three miscarriages, then met a man who offered her a good job to help her restart her life. In Bangladesh, Saba had followed a promise of work as a domestic helper, hoping to earn money to send back to her family, including a toddler son.

Traffickers prey on impoverished girls without a support network—they know no one will come looking, and they have no reason to fear the law coming after them.

Inescapable Violence

The brothel where these young women were sold is in a building notorious for holding minors and trafficked women. IJM has helped Mumbai Police conduct five rescue operations here over the past four years.

New girls were beaten by the brothel owners or starved until they “consented” to see a customer. The men start arriving around 4 or 5 in the evening, and the violence continues until 2 or 3 in the morning. Customers pay less than $4 for a turn with a girl.

(Read more about the harrowing rescue operation that set them free from this nightmare.)

On the night of rescue, one woman said, “The last three months I was in the brothel without seeing the sun or being outside, but somehow I was surviving.”

How IJM Provides Care From The Start—And Keeps Going

“This group of girls has an exceptional spirit. I sensed it from the night of their rescue,” says IJM trauma counselor Shalini Newbigging. She was there to provide crisis counseling, and she has continued to walk with the survivors since.

The young women settled into a private aftercare home in Mumbai as soon as they finished giving statements to the police that may be used in a criminal case against the four brothel keepers arrested that night. Though they woke up free the very next day, learning how to live free will take time.

IJM works closely with aftercare home staff to help survivors on this journey of freedom. Social workers assess each survivor’s unique needs, then create individualized treatment plans to address her physical, emotional, psychological and long-term vocational goals. Many of the aftercare homes provide education or job-training classes, and IJM often augments those services by hiring tutors or sponsoring seminars or health clinics that will benefit all of the girls in a home.

Certified counselors like Shalini provide invaluable services by offering one-on-one counseling to survivors, and by training staff in the homes and counselors from third-party agencies on how to provide effective trauma counseling. In one government home, there is just one counselor for 100 clients—a ratio that plainly shows how providers are often grossly under-resourced.

The Survivors Are Healing—And Dreaming—Thanks To New Role Models

Within a week of arriving at the aftercare home, most of the survivors had enrolled in Hindi and English lessons. They have now started skills-training, learning to stitch by hand and sew on a machine. Several women want to return home to start a tailoring shop or get a job at a garment factory. A couple of the women are earning income right now, helping make key chains and jewelry that are the sold locally.

Saba says she wants to learn how to cut hair and apply make-up so she can work at a beauty parlor. She says she wants to make women beautiful. Shalini and the other social workers will continue to support Saba and the others, even as they move to new aftercare homes closer to their families in the coming months.

When asked what she wants to become, Saba lights up. She covers her broad smile with a corner of her green dupatta, the long scarf she wears over her shoulders like shawl. Then she says with a rush of excitement, “I want to be like Shalini didi, then maybe I can help other girls.”

In less than two months, Shalini has become didi—older sister—and a role model who shows how helping others can be beautiful.

*A pseudonym